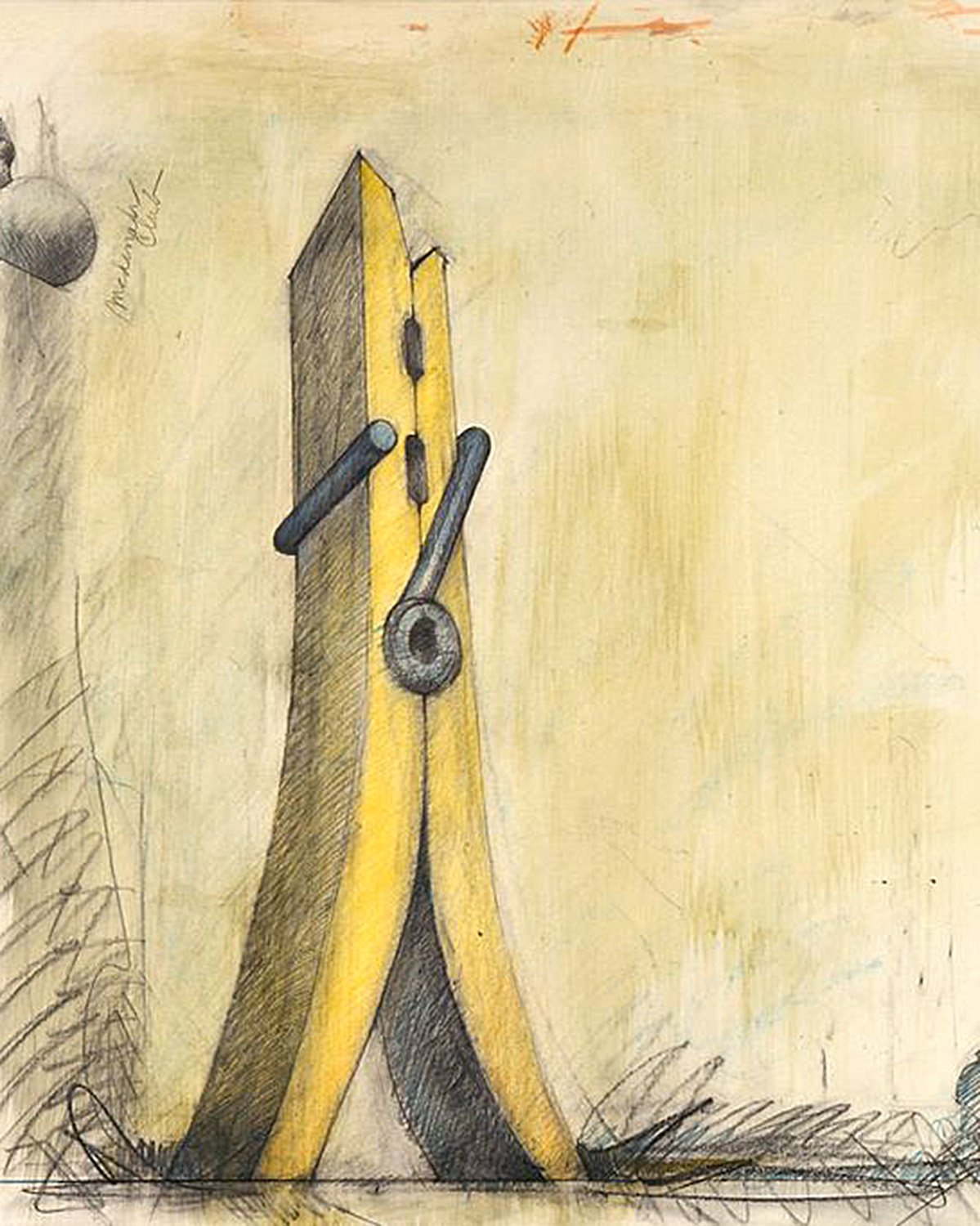

Claes Oldenburg made a powerful statement with his art, transforming everyday objects into monuments that astonish and delight us continually. The audacity and absurdity of a 45-foot-tall steel clothespin as a public statue is both ridiculous and profound, considering the huge task of designing, fabricating and mounting the piece in the center of a major city. How do you get from the sketch of a thought to technical drawings, to the engineering design needed to secure the 10-ton sculpture on its illuminating platform, to contracting and working with the steel fabricators? Who knows how many other hurdles had to be jumped. Sheer confidence and dedicated work is the only way to realizing such an idea.

There’s a comedic aspect of his art because of the unexpected importance given to things we take for granted. His comments about art that “sits on it’s ass in a museum,” and art that is big and heavy and “stupid as life itself” indicate his strength of conviction and desire to make comments about our society by glorifying so many ordinary and highly recognizable tools, utensils, and gadgets into instant landmarks wherever they appeared. His works are popular and enduring, with a “life” unequalled by most marble and bronze statuary, and they stand well apart from most contemporary large scale art because they are so relatable to the public by comparison. A person who says “I don’t know what it is, but I know it’s art” when describing an artist’s work, would likely know exactly what an Oldenburg sculpture is, and would also likely enjoy the outrageous monumentality of an ordinary thing so boldly transformed into importance.

Oldenburg worked in collaboration with Coosje van Bruggen, his wife of 32 years, until her death in 2009. From 1981 on, he officially signed all his work with both his own name and van Bruggen's, and they often worked in collaboration with Frank Ghery and with other architects to integrate the sculpture most effectively in numerous projects around the world. The distinctive look of the sculpture set it apart from most contemporary art from the beginning in the 1960s with his first efforts to be iconoclastic and depart from tradition. Even among POP art works, the giant flashlight or the giant saw stuck in the ground and many other such instantly familiar but strange monuments established a territory in the art world that only Oldenburg works could occupy.

Oldenburg works of the 1970s, when the focus on mundane objects began, influenced me the most. I made objects such as telephones and clocks with hot glass in reaction to the boldness of Oldenburg works. The simplicity of the objects and the shock of such a thing being so real, not just a drawing or a painting for example, inspired me to explore my own sense of societal observation to find meaningful images worth articulation as objects. I’ve never made anything that looks like an Oldenburg sculpture, but the attitude I explored has remained in my art. This pushed me far away from the use of glass in the traditional manner, and it led me to invent and adapt many ways of working with the materials I now use in realizing my ideas.

Oldenburg’s passing closes a chapter in art history that marks a generational change. Considering the art world of today with so many attempts by galleries and museums to exhibit artist’s works that have been “marginalized,” and widely common attitudes pushing trends of certain styles and “looks,” the subjective notions addressed by Oldenburg no longer have much presence in contemporary art. But Oldenburg’s art remains apart from the mainstream, and the sculptures will exist for many decades to come, to delight and puzzle us with their distinctive power.

—Dan Dailey